Writers and computers share a common trait: a fussiness about words. Writers choose their words with care. Computers are selective about the words they notice as well.

Metadata helps computers understand writing. Writers should care about metadata. Metadata influences how their writing connects to audiences. Metadata is an important editorial tool, though writers often don’t appreciate the value it offers.

I can hear some writers saying: “Hold on! — That’s not my job. I don’t know anything about metadata — I studied literature in college.” Metadata sounds like the antithesis of creative flair. And in some ways it is. I want to assure my friends who are writers that I’m not trying to turn them into geeks. Instead, I want to suggest that by having a little understanding of the geeky side of content, they can be more successful as writers.

Metadata, put very simply, is computer code that explains the meaning of content. That computer code can seem forbidding. But such code offers practical benefits to writers, and helps make content more interesting.

Writers should think about metadata as a form of communication, just as pantomime and poetry are. Metadata expresses ideas that are conveyed to audiences.

Metadata is a special form of communication, however, Unlike pantomime, metadata is purpose-built for the web.

Metadata as Describing

The most common type of metadata is the description. All web articles have META descriptions, which are short pithy statements summarizing the article. These statements often appear below the article title in Google search results. How well they are written can influence whether someone clicks on the link to read the article. Descriptions, by their nature, involve editorial decisions.

Another important description relates to photographs. Writers need to tell people what’s in a photograph. If the description is boring and vague, why would people want to view the photo? Describing visuals is becoming more important as people switch off their screens, and have content read aloud to them.

Metadata plays a valuable editorial role. It indicates what’s important about the content. Let’s consider some areas where metadata can help writers.

Suppose you are a film critic. You’ve quit a boring job writing training manuals about industrial equipment, and can finally use your literature degree in your work. Even as a film critic, you can amplify your writing by using metadata. Contrary to what you might expect, metadata can help writers tell stories.

Let’s imagine you want to review a new French film about the painter Paul Cézanne. The first conundrum is deciding how to refer to the film. Do you use the original French title, Cézanne et moi, or the translated English title, Cezanne and I? Fortunately, by using metadata, you can skirt this decision, by including the titles in both languages. Metadata can indicate the language of content. Someone in France could use language metadata to locate English language reviews of this French film, and compare them with the French language reviews. Do French and English speaking critics rate the film in the same way?

Another decision might be how to categorize the theme of the film. As a writer, you want your review to appear with other reviews about similar themes. Is the film about friendship, or is it a buddy movie? These terms relate to a concept in metadata called controlled vocabulary values. The writer needs to decide whether the theme is more about the friendship between two men, or about friendship generally. The decision will influence who sees the review, based on their interests and expectations.

Metadata can describe many aspects of a film, such as all the cast and crew involved. Writers might wonder, how interesting is all this information?

From the audience perspective, some information will be interesting to almost everyone, while other information is of interest only to committed fans. For some, detailed information seems like a list of dry facts. But for those who enjoy a film, the credits at the end provide extra value that enriches their experience.

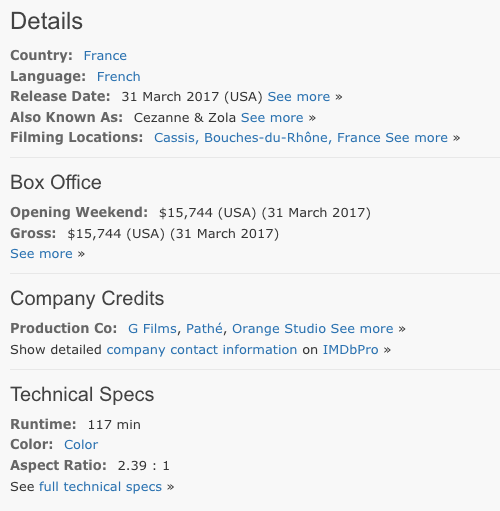

We can see the different editorial dimensions of metadata in the IMDb entry for the Cézanne film. (IMDb, the Amazon owned database, uses metadata extensively. But I’ll hide the code, and show only what’s presented on the screen.)

First, we have the storyline, or plot summary. Several sentences describe the film. To audiences, this is what’s important. Does the film sound interesting or boring? What is it really about (beyond friendship)? Audiences need to know if the film is potentially interesting before they will care enough to read a critique of it.

Metadata and Prose

The metadata for the storyline is prose, in contrast to the list of names of cast members. Some content strategists consider such prose as an unstructured “blob” — long passages, full of details, that aren’t broken out into a list or table. But it is a mistake to view prose content as being beyond the reach of metadata. Structuring content by breaking it into sections is a separate activity from adding metadata to content. Writers don’t need to “structure” their content into a list, table or other tightly defined unit to take advantage of metadata. Writers can, and should, add metadata to their prose. By doing so, they will highlight some of the most interesting material. Metadata is not a straight-jacket that limits how writers express their perspectives. Writers can write words, sentences and paragraphs as they please, and then add metadata to highlight important people, places and things mentioned in their text.

We can see in the storyline that the film concerns not only the painter Paul Cézanne (which we knew from the film title), but also the writer Emile Zola. After reading the storyline, people may be interested in learning more about the film, or may want to learn more about the subject of the film. Metadata can link this review to other writings related to the film in some way. Perhaps readers want to read reviews about other films concerning Paul Cézanne, or concerning the same time period. Metadata acts as a curator: linking to writings on related topics.

Let’s turn to the more fact-oriented metadata. To many writers, this material is dull. Because it is presented in a list or in a table, and deals with minutiae such as film duration and release date, the content seems to offer little editorial interest. Unless you are a big fan of someone in the film, or collect obscure facts to win pub quizzes, why would someone care about these details?

Stories from Metadata

For the writer, such detailed metadata presents an opportunity to tell more stories. It may not be immediately obvious, but some of the details are unusual, or notable for some reason. Since these details are described in a way computers can understand, the writer can easily compare these details with details for other films. The writer can tell readers what’s significant about the film — in terms of casting, location, historical firsts, or contribution to overall performance for different kinds of film.

Metadata offers writers a lens to think about different dimensions of a topic. By identifying various characteristics, metadata highlights connections between two or more of them. This film is one of a number of friendship-themed movies that use the musical composition ”Roses of Picardy” by Haydn Wood. (Other films include A Passage to India, and Charlie Brown’s Halloween special.) What’s going on with this use of music? There’s a story there, somewhere.

Metadata can bring attention to details that might not otherwise be noticed. Writers can use metadata to discover and highlight details of interest to audiences.

Metadata can be a writer’s friend. It can help writers tell stories. Writers, for their part, can help computers appreciate their words and ideas by using metadata.

To become friends with metadata, writers will want to know more about how to create metadata and include it in their content. They can learn about how that’s done in my new book, Metadata Basics for Web Content. Read the book, so the content you write will be content that is read. Make it your job to identify metadata that will connect audiences with your writing.

— Michael Andrews